The Asbjornson Sisters

- Cathy Josephson

- Sep 13, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Sep 15, 2025

By Cathy Josephson

Cathy volunteers for Icelandic Roots and also at the East Iceland Emigration Center in Vopnafjörður. She also serves on the board of Sögufélag Austurlands (Saga Society of East Iceland).

After the 1875 Aska eruption, many people in the East Fjords decided to leave Iceland for North America. A few people left earlier, but the trickle became a steady stream in 1876. Ættir Austfirðinga (Families of the East Fjords) indicates that they went “til Am” (to Amerika) without a word more, with few exceptions. Júníus H. Kristinsson‘s Vesturfaraskrá 1870-1914[1] records those who left from all of Iceland, listing 14.268 emigrants. Over the past 15 years, Icelandic Roots genealogists have accomplished further research of ship passenger lists and immigration records in North America to increase the number of emigrants from Iceland to nearly 17,000.[2]

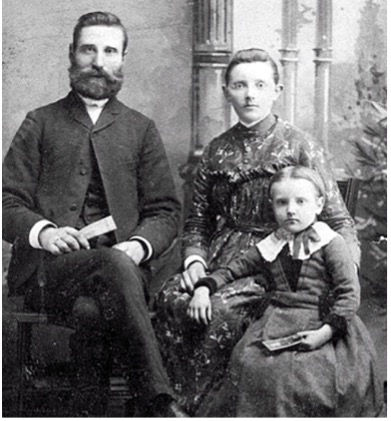

One who left East Iceland was Ásbjörn Jónsson (I520189)[3], born in 1821 at Hróaldsstaðir in Hofssókn, who was the son of Jón Sveinsson (I354134) and Guðríður Arngrímsdóttir (I88709). In 1847, he married Sigríður Ásbjörnsdóttir (I520190)[4], born in 1829 at Einarsstaðir in Hofssókn. They had 13 children, but six died young. Ásbjörn and Sigríður left for America in 1883 with their daughter, Sesselja. Four children had left Iceland between 1878 and 1879, and the last two daughters left in 1884.[5] [6]

Their son Jósep (I3445274) married Ólöf Steinunn (I577792) in 1877, the daughter of Valdimar Sveinsson and Kristín Jónsdóttir.[7] On July 1, 1879, the S.S. Camoens sailed from Vopnafjörður. Jósep Ásbjörnsson (1850-1902) and Ólöf Steinunn Valdimarsdóttir (1845-1945) and their two children were on their way to Minnesota.[8]

In June 1885, Jósep registered his homestead land in Lincoln County: 80 acres of Section 26 in Limestone Township, paid $4.00 registration fee[9], and farmed the land until his death in 1902. It was good land. In 1900, Jósep sowed ten acres of barley that spring, harvested and planted a second crop. In November, he brought samples of the barley, with heads from 3-4 inches long, to the newspaper in Minneota.[10]

Jósep and Ólöf (Olive) were blessed with eleven children; six reached adulthood. Sigridur Johanna (I577793), Octavia Bjorg (I577797), Oscar Joseph (I577799), Asbjorn Agust Eric (I577800) and Olof Florence (I577802) moved away to Montana and Oregon. A few years after Jósep‘s death, Ólöf moved to Minneota and later to Montana, where she died in 1945.

Valdimar (I577795), born at Krossavík in Vopnafjörður, farmed the land after his father‘s death. On 8 June 1903, Valdimar (known as Walter) and Oline (Lena) Vilhelmine Bang (I577826), born 1880 in Nyborg, Denmark, married at the Lincoln Icelandic Church and made their home on the family farm. Their five children were born and raised there and attended school in the village of Ivanhoe, a few miles away. Virgil Leon (I577827), born in 1905 and died in 1958, and Wallace Joseph (I577828), born in 1906 and died in 1970, never married. Carvel Oscar (I577820) was born in 1909, married Pearl Christensen, and died in 1990. Mildred Jonita (I577829) was born in 1907, and Adeline Loretta (I577831), the youngest, in 1917. The three brothers were lifelong residents of Lincoln County. But the Asbjornson sisters had wider plans.

Mildred was in Minneapolis in 1930, where she learned stenography before moving to Washington, D.C. She was first employed at the Veterans Administration, then the Department of State (1931-1968). Adeline joined her in 1939 and was a secretary at the Department of Labor and later for a legal firm. The sisters lived on California Street in Washington, D.C. until their retirement.

In 1933, this notice appeared in the Ivanhoe Times newspaper: “Mr. and Mrs. W. J. Asbjornson of the village of Ivanhoe received communication this week from their daughter Mildred, who is employed in Washington, D.C., reporting her promotion to secretary in the office of the Assistant Secretary of State.”

Millie, as everyone called her, served as personal secretary to many U.S. Secretaries of State from 1933 until her retirement in 1969, including Cordell Hull, James Byrnes, George C. Marshall, John Foster Dulles, Christian Herter, and Dean Rusk. Her life often included long hours and difficult circumstances, but also many interesting people, places, and experiences. In Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1933, for a conference, she met President Franklin D. Roosevelt—and had the pleasure of tasting Argentine beef (which she felt was the best in the world) and her first papaya. In Paris with Secretary James Byrnes in 1946, she returned to work to find a soldier carrying a heavy typewriter to Byrnes‘ office. Apparently, Byrnes had asked for a typewriter, and the soldier took it literally. What Mr. Byrnes needed was a stenographer.

At a conference in Bogota, Colombia, in 1947, Millie came face to face with a real “shoot-to-kill” revolution touched off when defeated presidential candidate, Jorge Eliecer Gaitan, was murdered. One of Millie‘s fellow workers wrote, “We looked down on funeral after funeral passing the hotel, and one day four truckloads of bodies passed. It is unbelievable that people can do such terrible damage to their own city and country. They hacked all that they could see. All the streetcars were burned, and cars turned over and burned.”

Jawaharlal Nehru died in 1964 in New Delhi. Millie‘s phone rang: “Can you be ready in 5 hours to fly to India with Secretary Rusk? ” The only answer was, “Of course!” Just time for a hair appointment and take what clothing was at hand. Another call after a few minutes—departure after three hours. Forget the hairdresser and throw clothes in a suitcase. She was on her way by noon on what turned out to be a trip around the world—in eight days, not eighty as in the movie. Madrid to Tehran to New Delhi, then on the way home, Millie finally had time for her shampoo in Thailand. Then she carried on to Manila, Taiwan, and a few days of welcome rest in Hawaii.

Millie traveled often by ship, later in DC-6 planes, and finally in jets— the best of all. Often she saw only what was near the road to and from the airports. At other times, she visited the Taj Mahal in India, flew over Mont Blanc in Switzerland, saw St. Peter‘s in Rome, experienced the beauty of Paris, and witnessed the reception President Kennedy received in Berlin in 1963. Millie met many memorable people through her work in the State Department: Winston Churchill, President Chiang Kai-shek in Taiwan, US presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Lyndon B. Johnson, and Popes Pius XII and Paul VI. In a career of 37 years, she visited nearly 30 countries in all parts of the world.

At her retirement in 1969, a farewell reception was held in her honor. Dean Rusk presented Mildred with a Superior Honor Medal and an engraved Tribute of Appreciation for 37 years of service. In the photo taken that day, a small medal had been pinned on Mildred‘s dress. The honor was equivalent to Iceland‘s Order of the Falcon.

Mildred announced that she would not be writing memoirs, left Washington, D.C., and headed home to Ivanhoe in Lincoln County. Adeline also retired in 1969. The sisters shared a home on South Harold Street in their last years. They enjoyed gardening and flowers, reading, preparing good food, and quiet travels together. Old friends visited, though they often had trouble booking flights to Lincoln County, which still has no airport.

Mildred said little about her work, but did agree to speak to students at the vocational school in Canby, Minnesota. She closed by saying, “Much of the credit for any success I may have had I owe to my alma mater (Ivanhoe High School). To get along with people is absolutely vital to success, to smile even when it is difficult and to be cooperative and helpful toward everyone. Being a good listener is also a great virtue.”[11]

Mildred died in 1993 in Ivanhoe. A few months later, Adeline received a letter of

condolence from President Bill Clinton.

Adeline completed her schooling in Minnesota before moving to Washington DC in 1939. She worked for some time at the Ministry of Labor and later for a legal firm in the city. Millie and Adeline lived together all their lives, both in Washington, DC, and lastly in the small village of Ivanhoe in Lincoln County.

Adeline was an active member in Augustana Lutheran Church in Washington, D.C. and served some time as president of the Young Women‘s Missionary Society,[12] a group of young women in the church. Journeys to and from Ivanhoe were, for most people in the 1940s and 1950s, by train. On one of Adeline‘s trips on the Columbia line, the train left the track near Alida, Indiana. (This passenger service was run by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad company, which was the oldest and first public company for transporting goods and passengers by rail, from 1830 until 1987.) Adeline suffered minor injuries and, after a short stay in a nearby hospital, continued her journey.[13]

Adeline‘s work was less demanding than Mildred‘s, and she was able to help when Mildred hurried home to get ready for another work-related trip. She probably knew more about Mildred‘s trips and experiences than anyone else and was probably quite satisfied to travel vicariously after surviving a train accident.

Adeline died in 2008 in Hendricks, another small town not far from Ivanhoe. Both are

buried in the family plot in the Lincoln County Icelandic Cemetery. A memorial tree has been planted near the entrance with a memorial marker dedicated to the Asbjornson sisters.

******

Cathy‘s Comments:

The search for more information about the Asbjornson sisters revealed little more than birth and death, a few census records, a few public documents, and their obituaries. They had one brother who married, and finding his grandchildren led to finding Adeline and Millie—always “Millie” to her family. We met for lunch in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where I was handed a USB full of photos and files. Family was very important to the sisters, who attended family gatherings as often as possible. Smiles on official photos, but wider smiles in family photos. More smiles and lively conversation when their brother‘s grandson and his two daughters shared their memories of the Asbjornson sisters.

Sources

[1]) Vesturfaraskrá 1870-1914. Júníus H. Kristinsson. Sagnfræðistofnun Háskóla Íslands, Reykjavík, 1983.

[2]) https://icelandicroots.com/. Research by the Emigration Team and Genealogy Team volunteers.

[3]) Ættir Austfirðinga nr. 12132

[4]) Ættir Austfirðinga nr. 12162

[5]) Hofssókn kirkjubækur. Þjóðskjalasafn Íslands. https://vefsja.skjalasafn.is/geoserver/www/vefsja/index.html

[6]) Vesturfaraskrá s. 6, 14, 19.

[7]) Ættir Austfirðinga: Valdimar nr. 7764, Kristín nr. 12133.

[8]) Þjóðskjalasafn Íslands. Vesturfaraskrár. ÞÍ. Sýslumaðurinn í Norður-Múlasýslu og bæjarfógetinn á Seyðisfirði o0000 OB/1-4-1. 1879-1880. Mynd 68 af 78. Flutningssamningur nr. 178.

[9]) Lincoln County Register of Deeds, Ivanhoe, Minnesota, USA. Photo taken of entry in register (IMG_1352).

[10]) Minneota Mascot, Minneota, Minnesota. 16 Nov 1900.

[11] Speech to students of Canby Vocational-Technical School, Canby, Minnesota, after she had moved back to Ivanhoe, Minnesota. This included information about her travels and experiences, as included here.

[12] Washington, DC Evening Star, 4 Jan 1941.

[13] Chicago Tribune, Chicago, Illinois. 1 July 1947 and Washington D.C. Evening Star, 1 July 1947.